- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

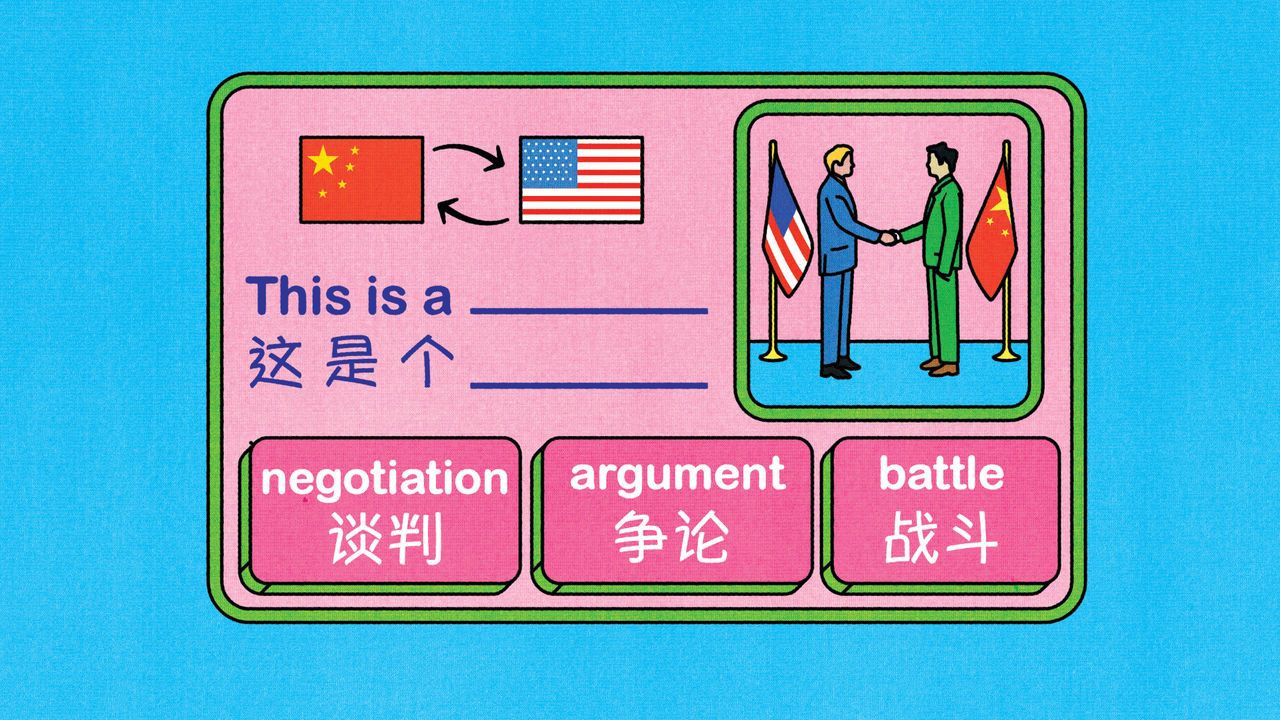

EVEN AS AMERICA’S relationship with China enters a , Donald Trump and Xi Jinping see the value in talking. On January 17th the leaders had a “very good” phone call, wrote Mr Trump on social media. Chinese diplomats said the two agreed to “keep in regular touch on major issues” and committed to work together for “world peace”.The language used during that exchange was simple enough. But communication between the powers isn’t always so straightforward. Words often mean one thing in English—and something quite different in Chinese. Ambiguous phrases can be used to send distinct messages to audiences in each country. Sometimes this leads to misunderstandings. Other times it may grease the wheels of diplomacy. At a time of rising tensions, linguistic sleight of hand is becoming more common and consequential in the Sino-American relationship.Take the phone call on January 24th between Wang Yi and Marco Rubio, the top diplomats of China and America. Mr Wang used the phrase , according to a summary of the event in Chinese from his government. The idiom might be used by a superior telling their subordinate to behave and consider the consequences of their actions. But it is vague. China’s foreign ministry has in the past translated it as “make the right choice” and “be very prudent about what they say or do”, according to the Associated Press, a news agency. The English summary of the account published by Xinhua, China’s official news service, does not include the phrase.Joe Biden liked to call China a “competitor”, which seemed less harsh than “opponent”, a term he used to describe Russia. But the distinction may be lost in China. Whereas the English word “competition” comes from the Latin for “strive together”, the Chinese equivalent in geopolitical contexts, , often sounds more zero-sum, meaning to struggle at the expense of one’s opponent. Earlier this year Kathleen Hicks, a deputy secretary of defence under Mr Biden, talked about these difficulties. After describing a policy of “deterrence” towards China, she noted that the word is often translated as , which literally means to terrorise with force. “So, I want to be clear,” added Ms Hicks, “we are not trying to coerce or compel [China].”Other complications arise because Chinese has fewer subordinate clauses than English and lacks articles such as “a” and “the”. This matters when Mr Xi vows that China will become “the leading power”—or is that “a leading power”? It depends whom you ask. Chinese state media translates it with the less threatening “a”, but many in the West use the definite article. Another challenge, says Chas Freeman, who translated for Richard Nixon during his visit to China in 1972, is that Chinese terms typically force a positive or negative valence. For example, it is impossible to call someone a defector in Chinese without indicating whether you deem them worthy of sympathy or scorn.The Communist Party thinks hard about the way it presents things in English. In 1998 it changed the name of its Propaganda Department to the more agreeable Publicity Department—but only in English. The One Belt and One Road Initiative quietly became the Belt and Road Initiative in 2015, making it sound less exclusive (the Chinese name did not change). Mr Xi, for his part, is usually called general secretary in Chinese, referring to his most important role as Communist Party chief. Chinese diplomats, however, insist that he be called “president” in English. This refers to his position as head of state. The presidential title confers less power than that of party chief (or chairman of the Central Military Commission, another job he holds). But it fits better with the nomenclature commonly used by other government heads.Translation has been an issue from the start of America’s formal relationship with Communist China. When establishing diplomatic ties in 1979, they signed a communiqué which in Chinese says that America “recognises” China’s position on Taiwan. In the English version, America merely “acknowledges” it. (Top American diplomats apparently did not check the translation.) Such linguistic dexterity is common. A study published in 2022 by Sabine Mokry of Leiden University in the Netherlands found that in almost half of the translated foreign-policy documents that China released from 2013 to 2019 there were differences between the English and Chinese versions that might change how a reader views the country’s intentions.When it comes to Mr Xi’s statements, one must often go beyond the literal translation. For example, he calls China’s technology sector his , or assassin’s mace. It sounds sinister when translated literally, but really means nothing more menacing than “trump card” or “ace up one’s sleeve”. Similarly, Mr Xi refers to the United Front Work Department, a body involved in boosting the party’s influence abroad, as his . (Mao Zedong did the same.) This is commonly translated as “magic weapon” by Western analysts and reporters. But it could also be understood as talisman,or protective shield.Scholars from America and China are working to agree on definitions for words that may one day appear in deals between the two countries. It’s not easy. In 2024 experts from the Brookings Institution, a think-tank in Washington, and Tsinghua University in Beijing published a glossary of terms relating to artificial intelligence. After years of discussion, they agreed on “joint interpretations” for just 25 of more than 100 proposed terms. Another effort, led by Arne Westad of Yale University, seeks to clarify words that describe when each country would consider using a nuclear bomb.Some flexibility with language may be worth maintaining, though. Mr Wang’s fuzzy warning to Mr Rubio allowed the government in Beijing to look strong before a domestic audience without alienating the new Trump administration. If any offence was taken as a result of the phone call, it may have been on the Chinese side. The State Department readout of the conversation misidentified Mr Wang’s job title. The error had nothing to do with language differences.