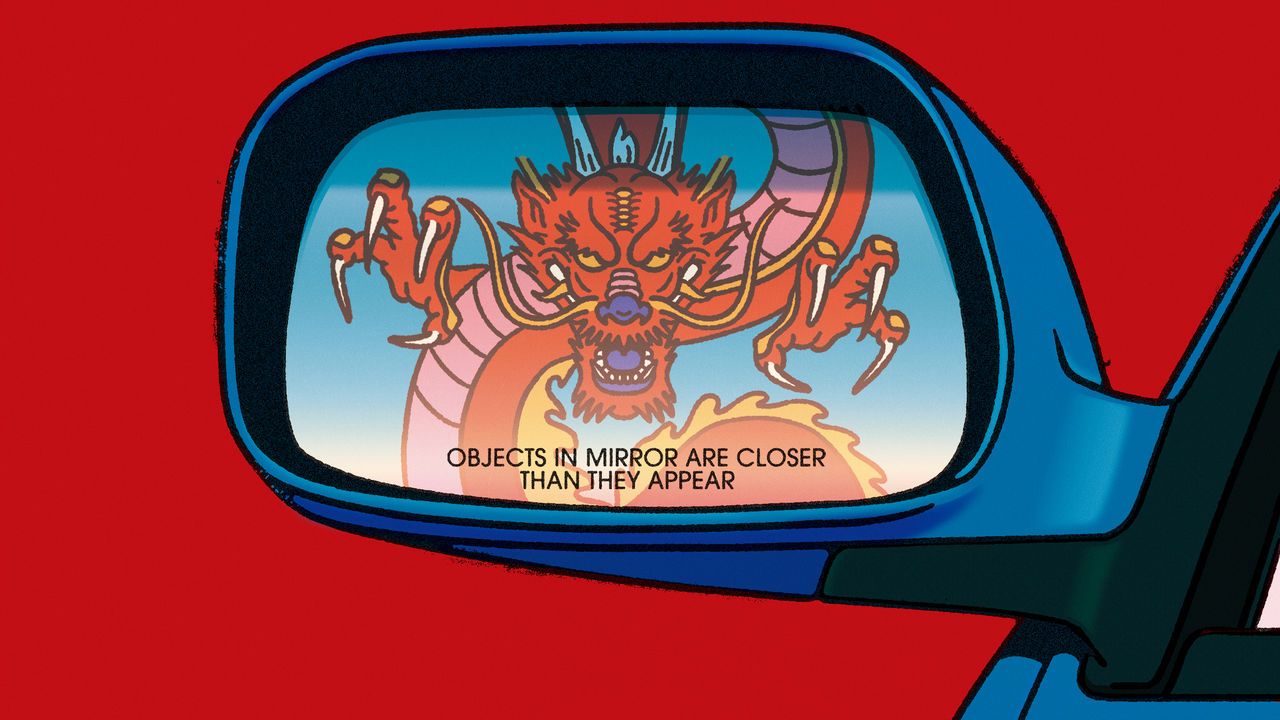

THE WORLD’sAIAIAIQQRAILLMAILLMLLMAIAILAIAIAIAILLMLLMERNIEGPTERNIEAIAILLMLLMAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIllmRAILLMLLMAIRAIAIQQAILLMLLMAIQQAIAIAIAIAIAIAIGPTAIPDAIYour browser does not support the element. first “reasoning model”, an advanced form of artificial intelligence, was released in September by Open, an American firm. o1, as it is called, uses a “chain of thought” to answer difficult questions in science and mathematics, breaking down problems to their constituent steps and testing various approaches to the task behind the scenes before presenting a conclusion to the user. Its unveiling set off a race to copy this method. Google came up with a reasoning model called “Gemini Flash Thinking” in December. Open responded with o3, an update of o1, a few days later.But Google, with all its resources, was not in fact the first firm to emulate Open. Less than three months after o1 was launched, Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce giant, released a new version of its Qwen chatbot, w, with the same “reasoning” capabilities. “What does it mean to think, to question, to understand?” the company asked in a florid blog post with a link to a free-to-use version of the model. Another Chinese firm, DeepSeek, had released a “preview” of a reasoning model, dubbed 1, a week before that. Despite the American government’s efforts to hold back China’s industry, two Chinese firms had reduced their American counterparts’ technological lead to a matter of weeks.It is not just with reasoning models that Chinese firms are in the vanguard: in December DeepSeek published a new large language model (), a form of that analyses and generates text. v3 was almost 700 gigabytes, far too large to run on anything but specialist hardware, and had 685bn parameters, the individual precepts that combine to form the model’s neural network. That made it bigger than anything previously released for free download. Llama 3.1, the flagship of Meta, the parent of Facebook, which was released in July, has only 405bn parameters.DeepSeek’s is not only bigger than many of its Western counterparts—it is also better, matched only by the proprietary models at Google and Open. Paul Gauthier, founder of Aider, an coding platform, ran the new DeepSeek model through his coding benchmark and found that it outclassed all its rivals except for o1 itself. msys, a crowdsourced ranking of chatbots, puts it seventh, higher than any other open-source model and the highest produced by a firm other than Google or Open (see chart).Chinese is now so close in quality to its American rivals that the boss of Open, Sam Altman, felt obliged to explain the narrowness of the gap. Shortly after DeepSeek released v3, he tweeted peevishly, “It is (relatively) easy to copy something that you know works. It is extremely hard to do something new, risky, and difficult when you don’t know if it will work.”China’s industry had initially appeared second-rate. That may be in part because it has had to contend with American sanctions. In 2022 America banned the export of advanced chips to China. Nvidia, a leading chipmaker, has had to design special downgrades to its products for the Chinese market. America has also sought to prevent China from developing the capacity to manufacture top-of-the-line chips at home, by banning exports of the necessary equipment and threatening penalties for non-American firms that might help, too.Another impediment is home-grown. Chinese firms came late to s, in part owing to regulatory concerns. They worried about how censors would react to models that might “hallucinate” and provide incorrect information or—worse—come up with politically dangerous statements. Baidu, a search giant, had experimented with s internally for years, and had created one called “”, but was hesitant to release it to the public. Even when the success of Chat prompted it to reconsider, it at first allowed access to bot by invitation only.Eventually the Chinese authorities issued regulations to foster the industry. Although they called on model-makers to emphasise sound content and to adhere to “socialist values”, they also pledged to “encourage innovative development of generative ”. China sought to compete globally, says Vivian Toh, editor of TechTechChina, a news site. Alibaba was one of the first wave of companies to adapt to the new permissive environment, launching its own , initially called Tongyi Qianwen and later abbreviated to “Qwen”.For a year or so, what Alibaba produced was nothing to be excited about: a fairly undistinguished “fork” based on Meta’s open-source Llama . But over the course of 2024, as Alibaba released successive iterations of Qwen, the quality began to improve. “These models seem to be competitive with very powerful models developed by leading labs in the West,” said Jack Clark of Anthropic, a Western lab, a year ago, when Alibaba released a version of Qwen that is capable of analysing images as well as text.China’s other internet giants, including Tencent and Huawei, are building their own models. But DeepSeek has different origins. It did not even exist when Alibaba released the first Qwen model. It is descended from High-Flyer, a hedge fund set up in 2015 to use to gain an edge in share-trading. Conducting fundamental research helped High-Flyer become one of the biggest quant funds in the country.But the motivation wasn’t purely commercial, according to Liang Wenfeng, High-Flyer’s founder. The first backers of Open weren’t looking for a return, he has observed; their motivation was to “pursue the mission”. The same month that Qwen launched in 2023, High-Flyer announced that it, too, was entering the race to create human-level and span off its research unit as DeepSeek.As Open had before it, DeepSeek promised to develop for the public good. The company would make most of its training results public, Mr Liang said, to try to prevent the technology’s “monopolisation” by only a few individuals or firms. Unlike Open, which was forced to seek private funding to cover the ballooning costs of training, DeepSeek has always had access to High-Flyer’s vast reserves of computing power.DeepSeek’s gargantuan is notable not just for its scale, but for the efficiency of its training, whereby the model is fed data from which it infers its parameters. This success derived not from a single, big innovation, says Nic Lane of Cambridge University, but from a series of marginal improvements. The training process, for instance, often used rounding to make calculations easier, but kept numbers precise when necessary. The server farm was reconfigured to let individual chips speak to each other more efficiently. And after the model had been trained, it was fine-tuned on output from DeepSeek 1, the reasoning system, learning how to mimic its quality at a lower cost.Thanks to these and other innovations, coming up with v3’s billions of parameters took fewer than 3m chip-hours, at an estimated cost of less than $6m—about a tenth of the computing power and expense that went into Llama 3.1. v3’s training required just 2,000 chips, whereas Llama 3.1 used 16,000. And because of America’s sanctions, the chips v3 used weren’t even the most powerful ones. Western firms seem ever more profligate with chips: Meta plans to build a server farm using 350,000 of them. Like Ginger Rogers dancing backwards and in high heels, DeepSeek, says Andrej Karpathy, former head of at Tesla, has made it “look easy” to train a frontier model “on a joke of a budget”.Not only was the model trained on the cheap, running it costs less as well. DeepSeek splits tasks over multiple chips more efficiently than its peers and begins the next step of a process before the previous one is finished. This allows it to keep chips working at full capacity with little redundancy. As a result, in February, when DeepSeek starts to let other firms create services that make use of v3, it will charge less than a tenth of what Anthropic does for use of Claude, its . “If the models are indeed of equivalent quality this is a dramatic new twist in the ongoing pricing wars,” says Simon Willison, an expert.DeepSeek’s quest for efficiency has not stopped there. This week, even as it published 1 in full, it also released a set of smaller, cheaper and faster “distilled” variants, which are almost as powerful as the bigger model. That mimicked similar releases from Alibaba and Meta and proved yet again that it could compete with the biggest names in the business.Alibaba and DeepSeek challenge the most advanced Western labs in another way, too. Unlike Open and Google, the Chinese labs follow Meta’s lead and make their systems available under an open-source licence. If you want to download a Qwen and build your own programming on top of it, you can—no specific permission is necessary. This permissiveness is matched by a remarkable openness: the two companies publish papers whenever they release new models that provide a wealth of detail on the techniques used to improve their performance.When Alibaba released w, standing for “Questions with Qwen”, it became the first firm in the world to publish such a model under an open licence, letting anyone download the full 20-gigabyte file and run it on their own systems or pull it apart to see how it works. That is a markedly different approach from Open, which keeps o1’s internal workings hidden.In broad strokes, both models apply what is known as “test-time compute”: instead of concentrating the use of computing power during the training of the model they also consume much more while answering queries than previous generations of s (see Business section). This is a digital version of what Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist, called “type two” thinking: slower, more deliberate and more analytical than the quick and instinctive “type one”. It has yielded promising results in such fields as maths and programming.If you are asked a simple factual question—to name the capital of France, say—you will probably respond with the first word that comes into your head, and probably be correct. A typical chatbot works in much the same way: if its statistical representation of language gives an overwhelmingly preferred answer, it completes the sentence accordingly.But if you are asked a more complex question, you tend to think about it in a more structured way. Asked to name the fifth-most-populous city in France, you will probably begin by coming up with a longlist of large French cities; then attempt to sort them by population and only after that give an answer.The trick for o1 and its imitators is to induce an to engage in the same form of structured thinking: rather than blurting out the most plausible response that comes to mind, the system instead takes the problem apart and works its way to an answer step by step.But o1 keeps its thoughts to itself, revealing to users only a summary of its process and its final conclusion. Open cited some justifications for this choice. Sometimes, for instance, the model will ponder whether to use offensive words or reveal dangerous information, but then decide not to. If its full reasoning is laid bare, then the sensitive material will be, too. But the model’s circumspection also keeps the precise mechanics of its reasoning hidden from would-be copycats.Alibaba has no such qualms. Ask w to solve a tricky maths problem and it will merrily detail every step in its journey, sometimes talking to itself for thousands of words as it attempts various approaches to the task. “So I need to find the least odd prime factor of 2019 + 1. Hmm, that seems pretty big, but I think I can break it down step by step,” the model begins, generating 2,000 words of analysis before concluding, correctly, that the answer is 97.Alibaba’s openness is not a coincidence, says Eiso Kant, the co-founder of Poolside, a firm based in Portugal that makes an tool for coders. Chinese labs are engaged in a battle for the same talent as the rest of the industry, he notes. “If you’re a researcher considering moving abroad, what’s the one thing the Western labs can’t give you? We can’t open up our stuff any more. We’re keeping everything under lock and key, because of the nature of the race we’re in.” Even if engineers at Chinese firms are not the first to discover a technique, they are often the first to publish it, says Mr Kant. “If you want to see any of the secret techniques come out, follow the Chinese open-source researchers. They publish everything and they’re doing an amazing job at it.” The paper that accompanied the release of v3 listed 139 authors by name, Mr Lane notes. Such acclaim may be more appealing than toiling in obscurity at an American lab.The American government’s determination to halt the flow of advanced technology to China has also made life less pleasant for Chinese researchers in America. The problem is not just the administrative burden imposed by new laws that aim to keep the latest innovations secret. There is also often a vague atmosphere of suspicion. Accusations of espionage fly even at social events.Working in China has its downsides, too. Ask DeepSeek v3 about Taiwan, for instance, and the model cheerfully begins to explain that it is an island in East Asia “officially known as the Republic of China”. But after it has composed a few sentences along these lines, it stops itself, deletes its initial answer and instead curtly suggests, “Let’s talk about something else.”Chinese labs are more transparent than their government in part because they want to create an ecosystem of firms centred on their . This has some commercial value, in that the companies building on the open-source models might eventually be persuaded to buy products or services from their creators. It also brings a strategic benefit to China, in that it creates allies in its conflict with America over .Chinese firms would naturally prefer to build on Chinese models, since they do not then need to worry that new bans or restrictions might cut them off from the underlying platform. They also know they are unlikely to fall foul of censorship requirements in China that Western models would not take into account. For firms like Apple and Samsung, eager to build tools into the devices they sell in China, local partners are a must, notes Francis Young, a tech investor based in Shanghai. And even some firms abroad have specific reasons for using Chinese models: Qwen was deliberately imbued with fluency in “low-resource” languages such as Urdu and Bengali, whereas American models are trained using predominantly English data. And then there is the enormous draw of the Chinese models’ lower running costs.This does not necessarily mean that Chinese models will sweep the world. American still has capabilities that its Chinese rivals cannot yet match. A research programme from Google hands a user’s web browser over to its Gemini chatbot, raising the prospect of “agents” interacting with the web. Chatbots from Anthropic and Open won’t just help you write code, but will run it for you as well. Claude will build and host entire applications. And step-by-step reasoning is not the only way to solve complex problems. Ask the conventional version of Chat the maths question above and it writes a simple program to find the answer.More innovations are in the pipeline, according to Mr Altman, who is expected to announce soon that Open has built “h-level super-agents” which are as capable as human experts across a range of intellectual tasks. The competition nipping at American ’s heels may yet spur it to greater things.