- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

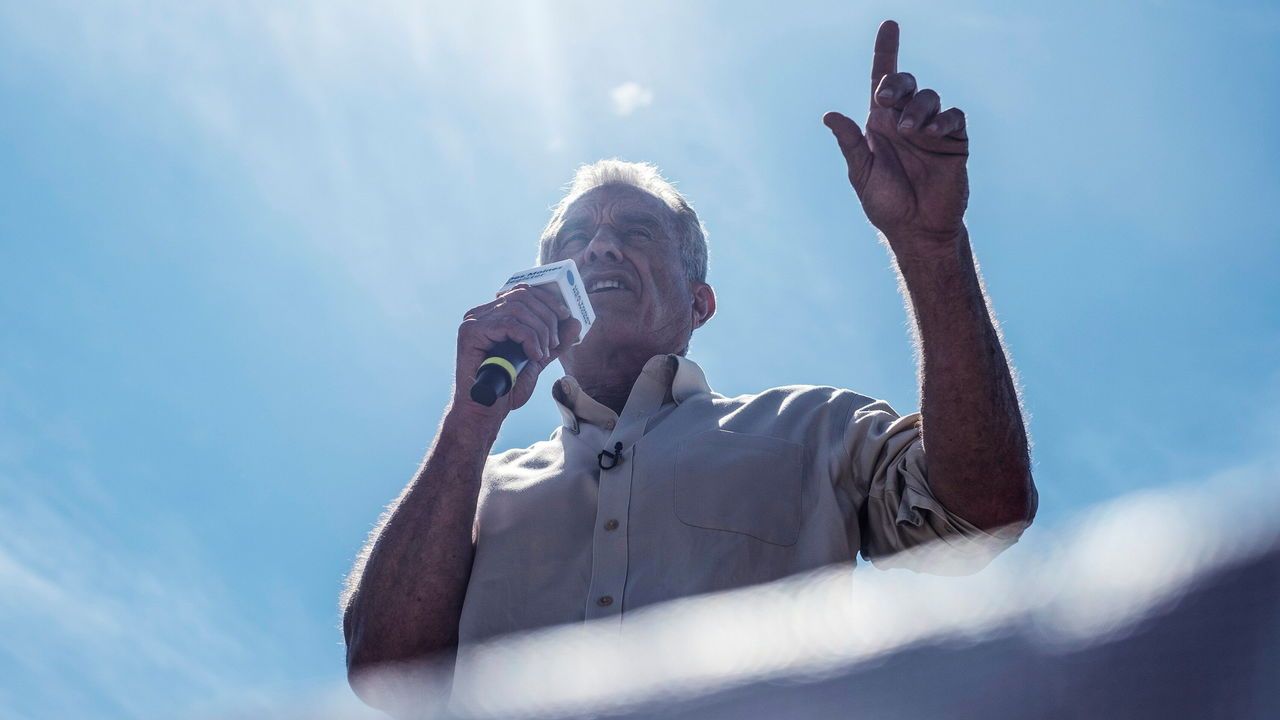

IT IS notMAHATVCDCMAHA GDPCDCFDANIHFDAFDANIHNIHNIHNIHUPFUPFNIHCDCMAHAMAHAX hard to construct a scenario in which Donald Trump’s plans to “Make America Healthy Again” (or ) do the opposite of that. His proposed secretary of health, , is one of the country’s more prominent vaccine sceptics. The man who would be in charge of the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which provides health coverage for two in five Americans, would be Mehmet Oz, a doctor who has talked about the medical benefits of communicating with the dead and invited a Reiki healer to assist him during surgery. Dave Weldon, a former congressman and doctor, who has also cast doubt on the safety of vaccines, would lead the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (), which oversees the country’s vaccine schedules. Unless the Nixon-to-China theory applies to public health, these are not the people America would want in charge of public health in a pandemic—or even just a regular epidemic.At the same time, a central part of the agenda is something most experts agree on: America’s main health problem is chronic diseases, and far too little is being done to prevent them. Mr Kennedy has some about how to tackle that. So it also is worth exploring what positive changes his tenure could bring about.About 60% of American adults have a chronic illness, such as diabetes, heart disease or cancer—40% have more than one. They cost America $3.7trn in 2016 (or 20% of) in medical spending and lost productivity. Yet America’s health-care system is focused on treating rather than preventing them. Mr Kennedy wants to from the American diet. He thinks the should be doing more about chronic diseases. And he wants a bigger share of government-funded research to focus on them. Done right, these are things that can put America on a healthier path.To achieve this ambitious agenda, Mr Kennedy, who does not have much experience running anything, would need to be clever about navigating the federal bureaucracy. He has talked about firing hundreds of staff, such as the entire nutrition department of the Food and Drug Administration (), and about pausing research on infectious diseases at the National Institutes of Health () to focus fully on chronic disease. In reality though, lots of government employees have civil-service job protection. And the existence of many departments is mandated by law. Congress also has a say on the distribution of funds within some of them.The things that prevent chronic diseases are no secret: healthy diets, less tobacco and alcohol, more sports at schools and better screening for precursors, such as high blood pressure, blood sugar or early signs of cancer. Of those, reforming America’s food system is closest to Mr Kennedy’s heart. He wants to purge the American diet of packed with additives such as artificial colours and other chemicals. But the federal food programmes with the biggest footprint are under the purview of the Agriculture Department. They include school meals (which 29m children benefit from) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme (formerly known as food stamps), which covers 42m people. The national dietary guidelines, coming up for review in 2025, are a joint production by the Health and Agriculture Departments. Brooke Rollins, the nominee for agriculture secretary, may bow to the many Republicans in Congress who are from farm states that stand to lose if potato crisps or the myriad foods sweetened with corn syrup are blacklisted.Mr Kennedy would have more control over on foods, which are regulated by the —especially if he sticks to his promise to shield health-policy making from corporate influence. More stringent regulation of the chemicals used in processed foods would force food companies to use fewer of them. But hiring the many more people that the would need for this is probably a non-starter in an administration bent on small government (to say nothing of Big Food’s influence in Congress). Standards for nutrient information on food packages that are designed with industry participation, as is the case in America, typically result in puzzling information and baffled consumers. Studies show that government bans on junk food advertising to children, for example, are more effective in cutting consumption than voluntary industry initiatives.But, as Mr Kennedy has acknowledged, changing what Americans eat is more complicated than telling them which foods are bad or restricting food-aid dollars to healthy foods. Fresh fruits and vegetables are rarely stocked by the corner shops where many poor Americans buy food; shelves there are laden with tobacco, alcohol and cheap processed foods because they are more profitable to sell. Programmes that have been found to boost the availability of healthy food in such fresh-food deserts typically involve some form of subsidy to shop owners. This sort of intervention could pay off in the long term but would be a hard sell politically, even if Mr Kennedy were to champion the idea.It is, though, the sort of intervention that Jay Bhattacharya, a Stanford University health economist picked by Mr Trump to lead the , could prioritise for research on the best ways to make people eat more healthily. That would fit with Mr Kennedy’s plans to shift research towards chronic diseases and nutrition, an idea with merit. Of the 11,000 research projects funded by the in 2012-2017 only 8.5% focused on studying prevention of the risk factors that account for 70% of deaths in America. Poor nutrition is the leading risk factor for ill health, but nutrition research accounts for just 4% of spending.This matters. When the expert committee in charge of updating America’s dietary guidelines convened in 2021 to discuss what to do with ultra-processed foods (s), it concluded that the research on their health effects was too thin to recommend anything specific. The world’s most rigorous clinical trial on how s affect health was done at the in 2019. Resources for such trials, however, were cut to the bone in 2022.If he is confirmed by the Senate, Mr Kennedy will quickly realise that to have a meaningful impact on chronic disease he needs co-operation from public-health services, which fall under the , and state health departments (to which the agency allocates 70% of its budget). They carry out campaigns to encourage people to eat healthy diets, stop smoking and drink less. They also run free clinics where people without health insurance get screened for cancer, diabetes and high blood pressure. For this sort of work, Mr Kennedy may not need to ask for a bigger budget.James Capretta from the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think-tank, reckons that, for all his talk, Mr Trump is not interested in pushing for any particular health policy—judging by how little he cared about health care during his first term. What the team will choose to pursue once in office is uncertain. In recent weeks Mr Kennedy has toned down his trashing of vaccines, even denying that he is opposed to them—no doubt to improve his chances of Senate confirmation. But once he bags the job, he could well focus a lot of his energy on anti-vaccine strategies. That would not make America healthy at all. As Jerome Adams, who was surgeon-general in Mr Trump’s first administration, wrote on , “Chronic diseases are important—but you can’t die from cancer when you’re 50 if you die from polio when you’re 5.”