- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

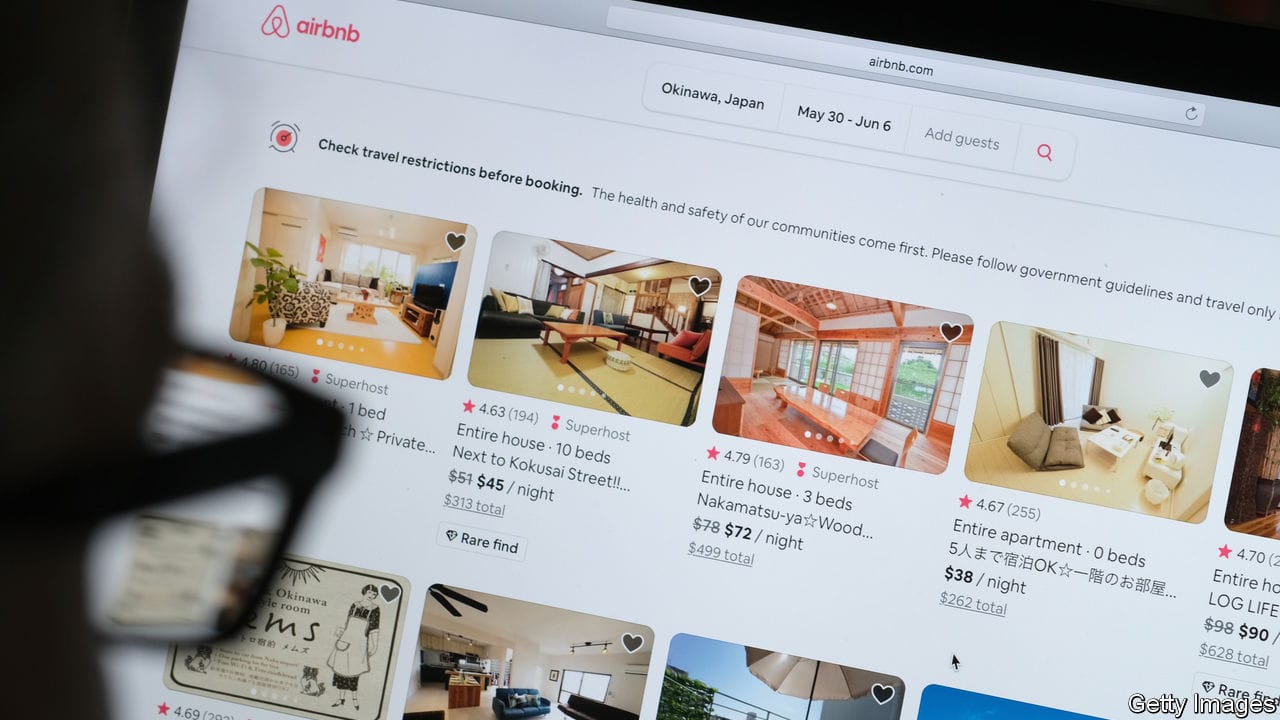

OVER THEVCIPOIPOIPOVC past two decades fewer firms in America have listed on the stockmarket, opting instead to stay in the shadows for longer. Entrepreneurs and venture capitalists (s) make two complaints. First, initial public offerings (s) are a rip-off. Second, the degree of outside scrutiny firms face can be uncomfortable. Now a new wave of tech firms are expected to go public, including Airbnb, a home-rental firm, and Palantir, which does data analytics (see ). Some plan to use one of two alternative techniques for floating: direct listings and blank-cheque companies. This disruption to the conventional market is risky but welcome. However, in the long run these newcomers won’t be able to escape ruthless outside scrutiny of their business models.The decline of s is striking. On average in the 25 years to 2000, 282 firms staged one each year, but since 2001 the figure has fallen to 115. This has made the economy more opaque and prevented ordinary people from investing in young firms. The underlying cause is a shift in the balance of power towards companies. Tech startups tend to be asset-light and need less capital, while the industry has grown and can fund firms for longer. Startups can thus delay going public. Amazon floated in 1997 when it was three years old, but the typical firm listing now is 11. There is a backlog of 225 unicorns—private startups worth over $1bn—which are supposedly worth a total of $660bn.