- by ATWATER, DALLAS AND SPOKANE

- 12 19, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

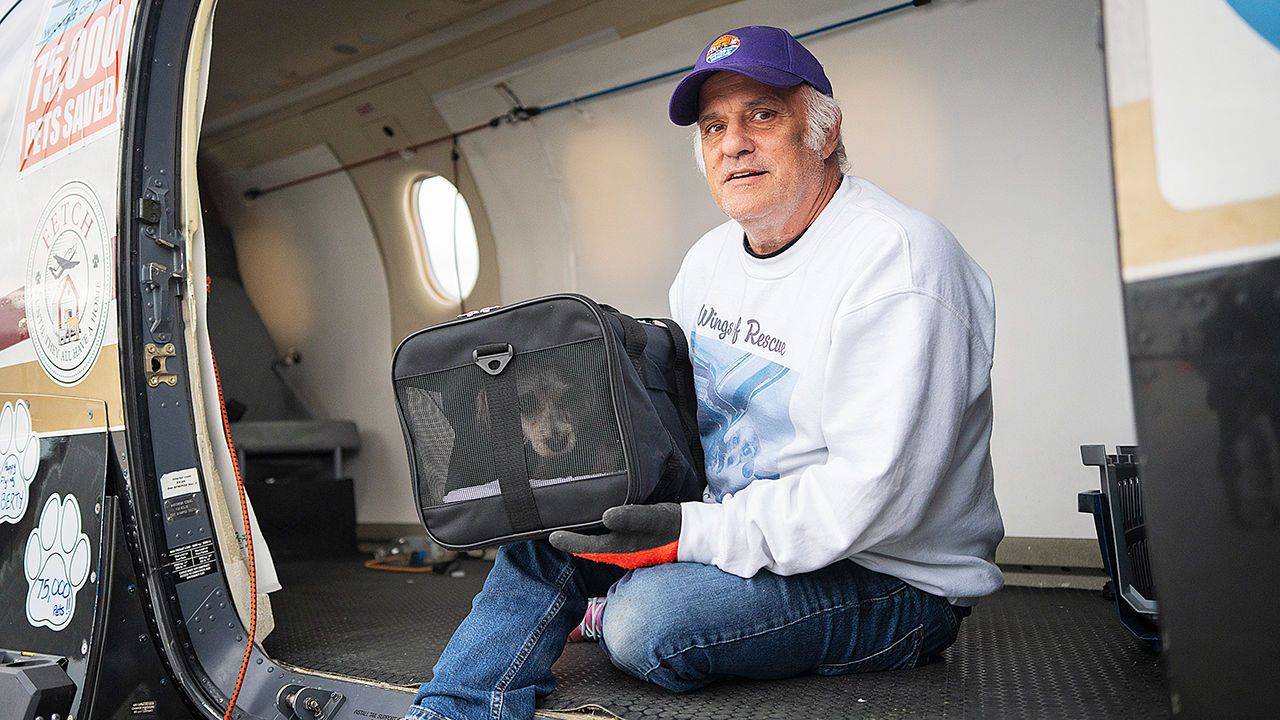

IT WAS AASPCAusASPCAASPCAASPCA crammed flight. Most of the passengers squirmed. Some whimpered. A few even cried. One barked complaints in the direction of the cockpit. In some ways this was not unlike a cut-rate trip on a budget carrier; in others it was exceptional. Everyone within eyeshot stared intensely at your correspondent, as if looking for an answer and assurance about what would happen next. The smell—a mix of dog and cat hair, urine, faeces and stress—was overpowering.This was a rescue mission. Crates carrying 101 animals—45 dogs and 56 cats—had just been loaded up at an airstrip in Atwater, in California’s Central Valley, an agricultural breadbasket-turned-economic wasteland. The small private plane, with a cargo hold where seats might have been, was about to fly to Washington state.“All these dogs and cats would be euthanised” were they to stay in the Central Valley, says Sharon Lohman, who is standing on the tarmac with Liberty, a small, silver, Washington-bound mutt with traces of schnauzer, in her arms. Liberty had been abandoned in an almond orchard on a piece of cardboard for weeks. “When you see an animal who stays in the same spot day after day after day, it’s been dumped, because it’s waiting for the owner to come back,” she explains.Ms Lohman, who worked at Disney before founding New Beginnings, an animal-rescue charity, did not want to see these animals die because no one local would adopt them. She called Ric Browde (pictured here with Liberty), a former music producer who runs Wings of Rescue, a charity that flies animals likely to be euthanised to places where they can find a home. He phoned contacts in Washington to see if they had space for any new animals. The answer was yes, so these lucky pets were set to travel some 1,500km (around 930 miles) by air with volunteer pilots, a husband-and-wife team based in Oregon, who own a plane and average around three rescue flights a month.In America an average of nearly 1m cats and dogs were euthanised each year from 2016-2019, according to Shelter Animals Count, a database. There were too many animals for the number of willing adopters. However, for the past two decades volunteers have been trying to reduce this death toll by banding together to whisk dogs and cats to safety. They function a bit like an “underground railroad” for pets, ferrying dogs and cats mostly from the South to the North.Some of these efforts are informal: shelter staff post notices on message boards asking pilots and truck drivers to help provide “freedom flights” and “rides to rescue” for animals in need. Others are more co-ordinated. The largest initiative, run by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (), relocates around 30,000 dogs and cats a year by truck and plane, including chartered flights each weekend; 43 people work on its programme. Wings of Rescue will organise around 50 flights this year: Liberty was the charity’s 75,000th pet to be taken to safety.Volunteers have formed bonds of trust and something approaching friendship. They often organise for handoffs to happen halfway to reduce each other’s travel burdens. The first stop on your correspondent’s flight, two-and-a-half hours after leaving Atwater, was Arlington, Washington. Volunteers from the Northwest Organisation of Animal Help, a charity, were waiting on the tarmac and greeted the pilots and Mr Browde with hugs and handshakes. Coos of admiration met the 38 cats and kittens, who were put in the back of a van. Liberty stayed on the plane.Another take-off. The animals were adjusting to the jet-setting and were quieter. Most slept. Liberty was curled up in her carrier. The next stop was Oroville, near the Canadian border. The tiny airstrip had only a small shed, which doubled as Customs and a toilet. A jaunty Canadian, Jeneane Rucheinsky of Our Last Hope Animal Rescue Society, was waiting. She could take only seven dogs. One, still wearing its pink collar and tags with its former owner’s details, looked morose as it was loaded into the boot of her van. Ms Rucheinsky double-checked the paperwork; she was driving to British Columbia and would have to report her passengers to Canada’s border patrol.Another 30 minutes by air, and Spokane was the final stop. The rest of the animals were taken out of the cargo hold and loaded onto a truck, bound for SpokAnimal, the local shelter. All would be spayed and neutered, and most would be adopted within a week.With the animals off, the pilots prepared to depart. “There are so many things in life that rob you of this or that, and this is one of those things that fills everybody up—everyone involved,” explains Kale Garcia, one of the pilots. “It gets you hooked.”Two days later, Theresa Fall, who has had eight dogs during her 48-year marriage, came to see Liberty. She had watched Wings of Rescue’s Facebook video, recorded in Atwater. It was not love at first sight: Liberty bit her. But Ms Fall understood Liberty had been “so traumatised” by being abandoned that it was not personal. What Liberty needed was a home; Ms Falls offered her one. Rescue animals “come with quirks and fears, but you just love it out of them,” she says. “And they become the most wonderful, thankful dogs. You can’t buy pedigreed dogs like rescue dogs.”Hurricane Katrina, which lashed New Orleans in 2005, flooded the public with news of human suffering, as well as images of displaced pets. Shelters across the country banded together to place homeless dogs and cats in other states. It gave people the idea that relocation could help “save animals across the country”, says Karen Walsh of the . Now charities often fly in before storms hit, to take animals elsewhere for adoption and free up space for newly displaced ones.Relocation is now key to non-profits’ and shelters’ strategies to help animals survive. Take the Humane Society of Cedar Creek Lake, a shelter in rural east Texas. Half of the 1,000 or so animals they take in each year are transferred to another shelter, mostly out-of-state. “This would be a miserable job, if we did not have transport,” says Jennifer Miller, who works there.Transports are logistically complex. Animals require health certificates to move across state lines; certain states mandate specific vaccinations and even quarantines. Relocation is also costly and so hard to scale. Operation Kindness, in Dallas, will spend about $1m to transport around 1,500 dogs and cats this year; in 2023 it spent $600,000 to move 1,000. Does anyone object to such high costs or the carbon footprint of rescue flights? Not really. “It’s puppies,” quips Mr Browde. No constituency of vocal environmentalists or fiscal hawks lobbies for them to die instead.From 2005 to 2020, the story was almost a fairy tale, with furry protagonists whisked to safety in the north. However, covid presented a dark plot twist. Shelters closed temporarily, and many spay-neuter procedures were put off for that reason, as well as a shortage of veterinarians and rising costs. The pandemic contributed to a deficit of more than 2.7m spay-neuter procedures, according to one academic study. Dog and cat populations have ballooned. “It’s easy to have an animal boom in a very short period of time. I think we’ve proved that,” says Ms Walsh of the .The cost-of-living crisis in America has also forced people to make uncharitable decisions about fur babies. Large dogs have been the hardest hit. Many landlords have imposed weight restrictions and bans on certain breeds. Animals are being dumped more often.Shelters in the North that once took truckloads of animals from the South can accommodate fewer today; they have no space. The will move around a third fewer animals this year than in 2019; Wings of Rescue’s flights are down by more than half. “Everything’s so rough in animal world” that shelters are jostling for space on transport missions and relying heavily on the hope of relocation to save their animals, says Ed Jamison, the boss of Operation Kindness.Dogs and cats offer a Rorschach test for human nature: do you focus on the positive or the negative? The bleak view is that people treat animals callously, abandoning them to starve or be hit by cars. Anji Kealing-Garcia, one of the volunteer pilots for Wings of Rescue, encountered a dog that had been surrendered at a shelter after a woman redid her living room’s upholstery and decided the colour of her dog clashed.People can be impulsive and faddish. Whole breeds come in and out of style. People rushed to adopt the spotted canines after the release and subsequent remakes of Disney’s “101 Dalmatians”. Today shelters are crammed with Siberian huskies. After “Game of Thrones” featured dire wolves, which are extinct, breeders and buyers decided huskies were the next best thing, only to find they require huge amounts of care, exercise and grooming.But shelter pets can also serve as a testament to human compassion and generosity. Americans will spend more than $150bn on their pets this year, around two-thirds more than they did in 2018. (That is more than the gross domestic product of around two-thirds of the world’s nations.) At Operation Kindness, your correspondent briefly pitied a small dog recovering from surgery after one eye was removed, only to be told that one-eyed dogs are adopted faster. “Everyone thinks they’re cute, and everybody feels bad for them,” says Colton Jones, a veterinarian. But “one-eyed dogs and tripods”, three-legged dogs, “are the first out the door.” Dogs and cats evacuated from hurricane zones are also adopted quickly. People empathise with their ordeals—and like to have pets with a unique story.Liberty certainly came with one. It took her a few days to settle in at the Falls’ home, eased by the calm companionship of another rescue dog, named Gus. “I sit back and think about all the people who made it possible for me to get this little dog,” says Ms Falls. She sends photos and updates to Ms Lohman in California to keep her posted on Liberty’s milestones, such as her first hike in Washington. (Liberty loved it.)It will take years, most agree, to deal with the fallout from this recent population boom. It leaves rescuers with a feeling of urgency. “Every time the door closes, you get this sense of joy. And you go ‘Oh wow, we did something cool’,” explains Mr Browde, after the daylong trip from California to Washington. “And then you think about the ones that didn’t make the flight, and you’re back in the doldrums again and think, ‘I’ve got to work harder next time’.”