- by Amy Yee

- 01 15, 2026

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

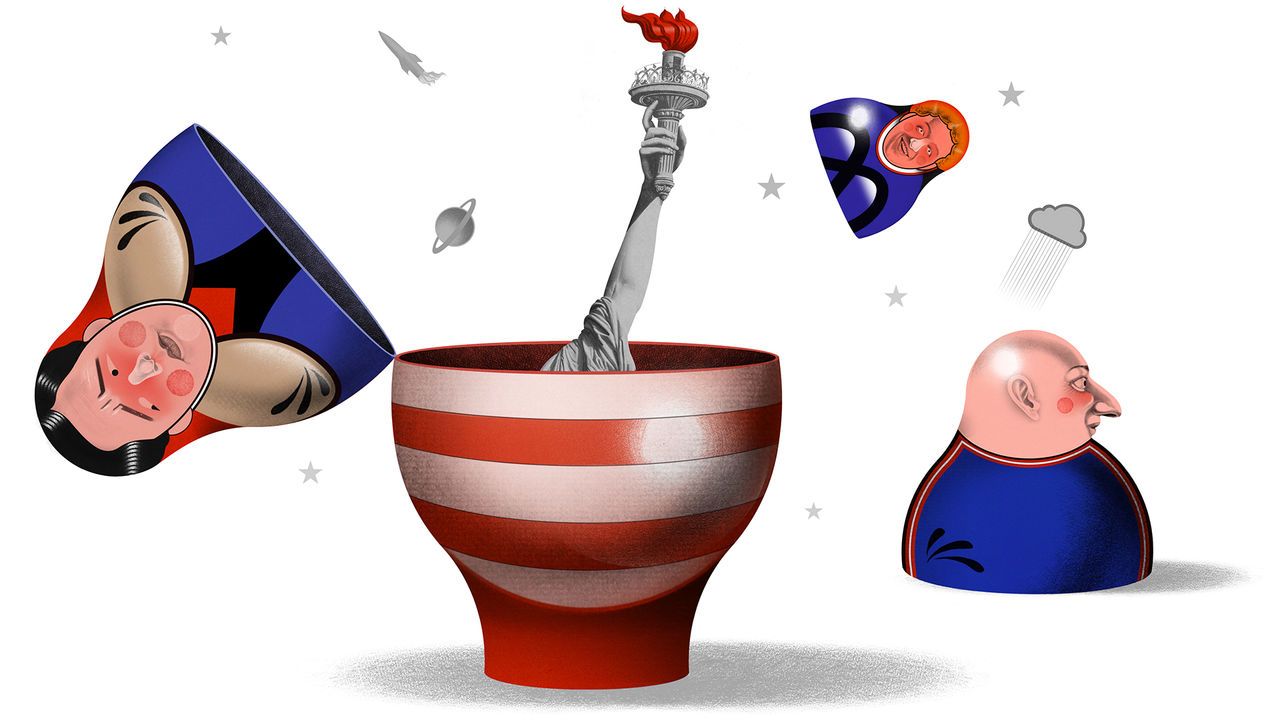

WHAT NATIONLVMH GDPCEOGDPMAGA can you fit into the Capitol Rotunda? Answer: somewhere between a Portugal and a Thailand. Each country’s total household net wealth was $1.3trn, give or take, according to the latest available figures from a few years ago. This is around the accumulated fortune of the billionaires who turned up for Donald Trump’s second presidential inauguration in Washington on January 20th. Bernard Arnault, owner of , aluxury empire, and Europe’s richest man, represented the old continent’s fat cats. Mukesh Ambani, an Indian industrialist who is Mr Arnault’s Asian opposite number, stood in for the global south’s.However, it was , Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg (collective net worth: $911bn, a bit shy of three Luxembourgs) who got the most attention—and better seats than the incoming cabinet. Only the Trump family stood between and the 47th president as he took the oath of office.This proximity to power—literal and figurative—alarms many. In his farewell address from the White House five days earlier Joe Biden warned that “an oligarchy is taking shape in America” and of a rising “tech-industrial complex that could pose real dangers for our country”. It is not just Americans who are worried. On January 18th Reuters reported that Germany’s ambassador to the United States, a sober Teutonic type not normally given to hyperbole, had confidentially alerted the government in Berlin that, among other disruptive moves by the second Trump administration, “big tech will be given co-governing power.”Inaugural seating arrangements notwithstanding, such assessments seem far too bleak. America is no oligarchy—and unlikely ever to become one, for three reasons. First, the supposed technoligarchs control far too small a portion of the country’s vast and vastly diverse economy to be able to influence its overall direction—one of the big fears behind warnings like Mr Biden’s.Although Mr Bezos’s Amazon, Mr Zuckerberg’s Meta and Mr Musk’s Tesla together account for one-tenth of the value of all listed stocks in America, their economic contribution is much more modest. This contribution, or gross value added, is calculated by adding a firm’s profits before net taxes and financing costs to what its employees earn in salaries and benefits. Companies seldom report their total wage bills but sales and general administrative expenses combined with research-and-development costs give a rough idea. Add this to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, and Amazon, Meta and Tesla correspond to 1.8% of American .Even if you add Apple and Alphabet, whose s also attended Mr Trump’s swearing-in but who are hired stewards rather than founder-owners and thus decidedly unoligarchic, the figure rises to just 3.1%. In Russia, home to the original oligarchs (in the non-ancient-Greek sense), the figure is much higher. A study from 2004 in the found that two dozen magnates employed nearly a fifth of all workers and earned 77% of sales in manufacturing and mining, which at the time accounted for two-thirds of Russian output. In Hungary, the closest the Western world has to a real oligarchy, chums of Viktor Orban, the strongman prime minister, may oversee 20-30% of the economy, according to one estimate.Other measures tell a similar story. Amazon, Meta and Tesla make up 9% of business investment by America’s 1,500 largest firms. In India, Mr Ambani’s accounts for 16%. The trio’s capital spending is equivalent to 0.4% of , compared with nearly 1% for John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil in 1906.The experience of Rockefeller points to another reason not to panic. Despite his immense wealth—at its peak almost twice Mr Musk’s relative to the size of America’s economy—he struggled to have his voice heard in the corridors of power, points out Tevi Troy, author of “The Power and the Money”, a history of American potentates’ rapports with commanders-in-chief. President James Garfield did not know how to spell his name.Even though Mr Trump is clearly friendlier to business than his trustbusting predecessors a century ago, his feelings towards tech do not seem to run deep. The word “technology” did not feature in his inaugural address (in contrast to “liquid gold”). Moreover, in America public opinion still matters, and could easily turn against the tech billionaires. Sections of already loathe them.Crucially, in contrast to Rockefeller, who wielded near-total control over a critical economic input in the form of refined petroleum products, they cannot hold the American economy to ransom. No Amazon? Walmart will happily sell you everything you need. Instagram says access denied? Great, then you have time to read Mr Troy’s riveting book. Want a new car? Tesla may anyway not be your top pick of vehicle these days. Even Mr Musk’s SpaceX rockets may not be the only game in town for ever, though Rocket Lab, the firm’s closest competitor, and Blue Origin, a company founded by Mr Bezos, are still some way behind. The rocket rivalry highlights the last reason for calm. Big tech is not a monolithic interest group, like the Russian oligarchs whose businesses mostly do not overlap. The technology tycoons’ interests are often in conflict. Messrs Bezos and Musk compete in space. Mr Musk and Mr Zuckerberg own rival social-media platforms. Amazon is taking a bite out of Meta’s online-advertising business. Everyone is piling into artificial intelligence.Mr Trump is more transactional than presidents before him, which increases the risk of cronyism and self-dealing. But America’s economy, including its technology industry, is too unwieldy and dynamic to petrify into an actual oligarchy, whatever diplomats and departing presidents say.