- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

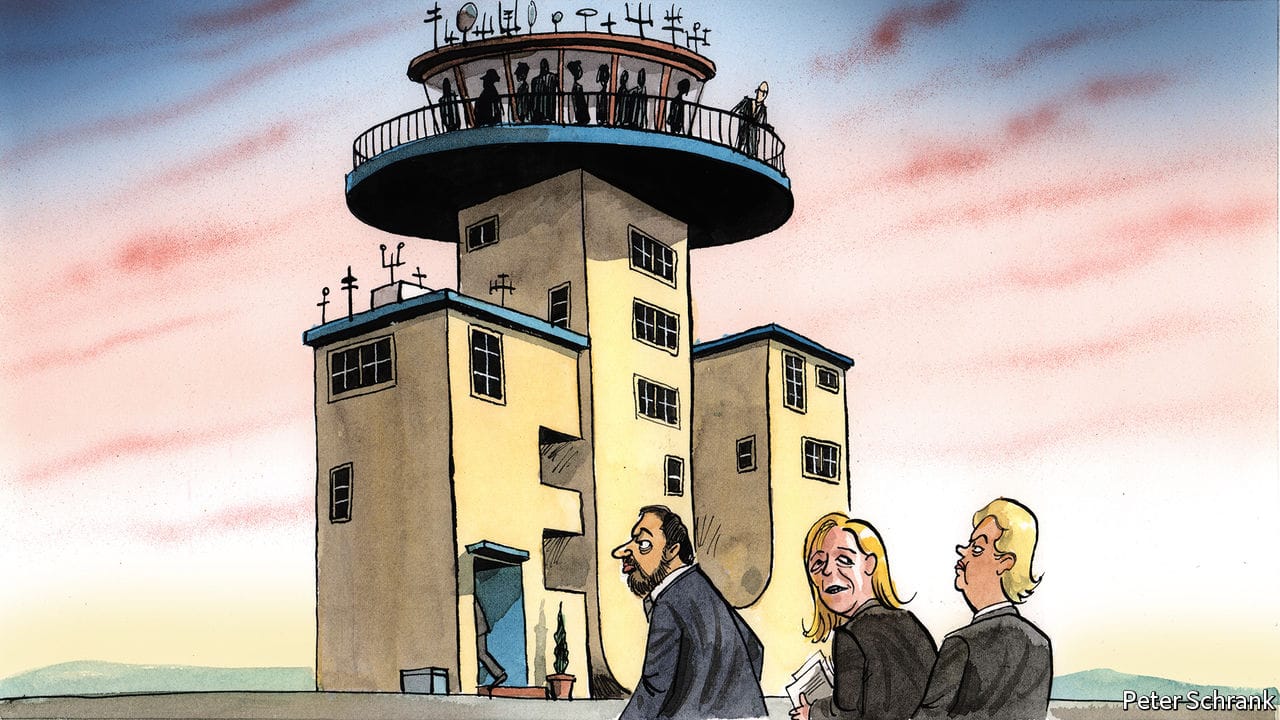

IN 2017, ANYEU.EUEUEUEUEU voters who wanted to follow Britain out of the had options In the run-up to elections that spring, Geert Wilders, a bizarrely coiffured advocate of “Nexit”, was level at the top of polls in the Netherlands. A few months later Marine Le Pen reached the second round of the French presidential election on a policy of taking the country out of the euro and the itself. In Italy, Matteo Salvini, the leader of the Northern League, attacked Mario Draghi, then the boss of Europe’s central bank, as an “accomplice” to the “massacre” of Italy’s economy. The party dangled the prospect of Italy’s departure from the euro and even the itself.Skip forward four years and the picture is different. Ahead of Dutch elections next week, there has been so little discussion of the that academics there have started begging politicians to pay some attention to the “ [elephant]” in the room. After flopping last time, Mr Wilders is now bashing Islam rather than Brussels. It will do him little good. Polls give a large lead to the party of Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, who has learned to stop worrying and (almost, but not quite) love the . After a comprehensive defeat at the hands of Emmanuel Macron in 2017, Ms Le Pen and advisers have dropped their calls for Frexit and abandoning the euro ahead of elections next year. In Italy, Mr Salvini now supports a technocratic government run by Mr Draghi, his former nemesis, who is now prime minister. “I am a very pragmatic person,” said Mr Salvini, when discussing the shift.