- by MAJDAL SHAMS

- 07 28, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

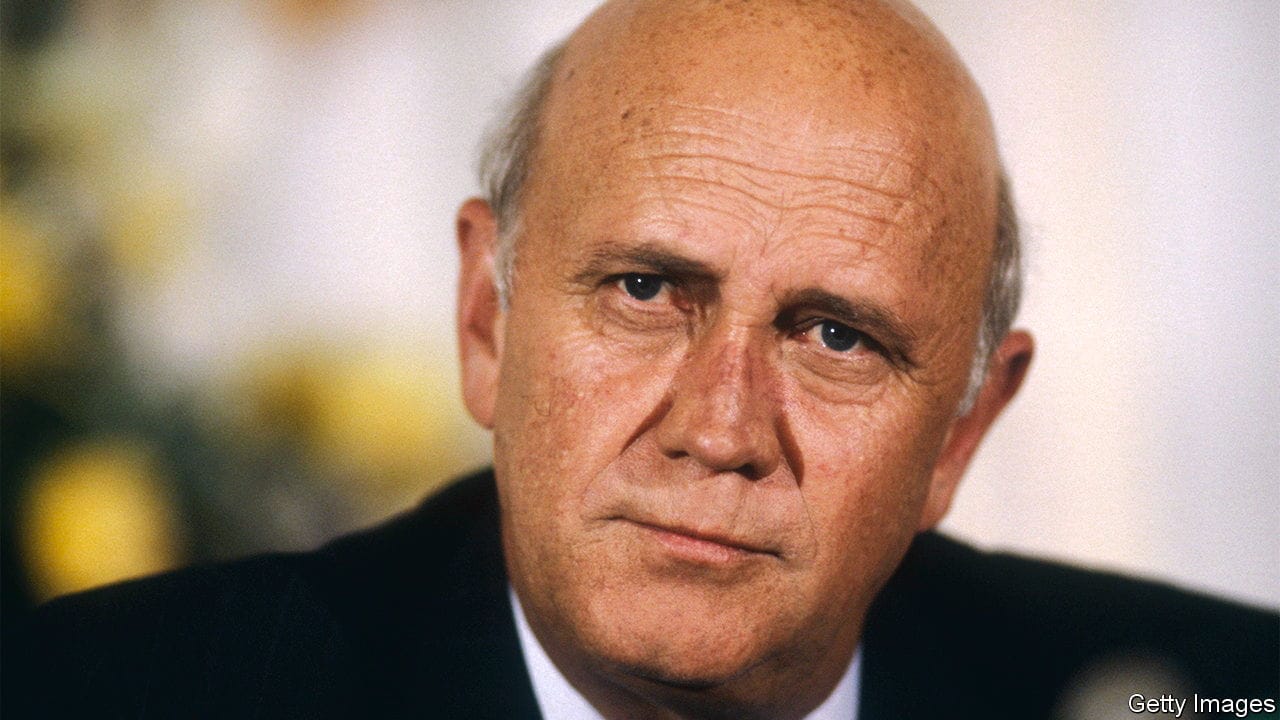

HE WAS slow and deliberate in his speech, like a (minister) of the conservative Dutch Reformed Church he had belonged to all his life. Grey, not just at his temples, but in his cautious, conciliatory manner. And the very epitome of conservatism, from his earliest days in student politics while studying law at Potchefstroom University, a bastion of Afrikanerdom where he edited the student newspaper, to his membership in the , a secret society of Afrikaner men dedicated to white rule. Nor could one see in his family any hint of the revolutionary that F.W. de Klerk was to become after his election as South Africa’s president in 1989.His grandfather was a in the most conservative branch of a church that provided a supposed theological justification for racial segregation. His father had served for many years as a government minister for the segregationist National Party. And his uncle, J.G. Strijdom, was a white supremacist who, as prime minister in the 1950s, was one of the main architects of South Africa’s system of racial rule, known as apartheid. Even his brother, Wimpie, a liberal Afrikaner who opposed segregation, thought Mr de Klerk would be too conservative a president to reform the country and end its international isolation.