- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

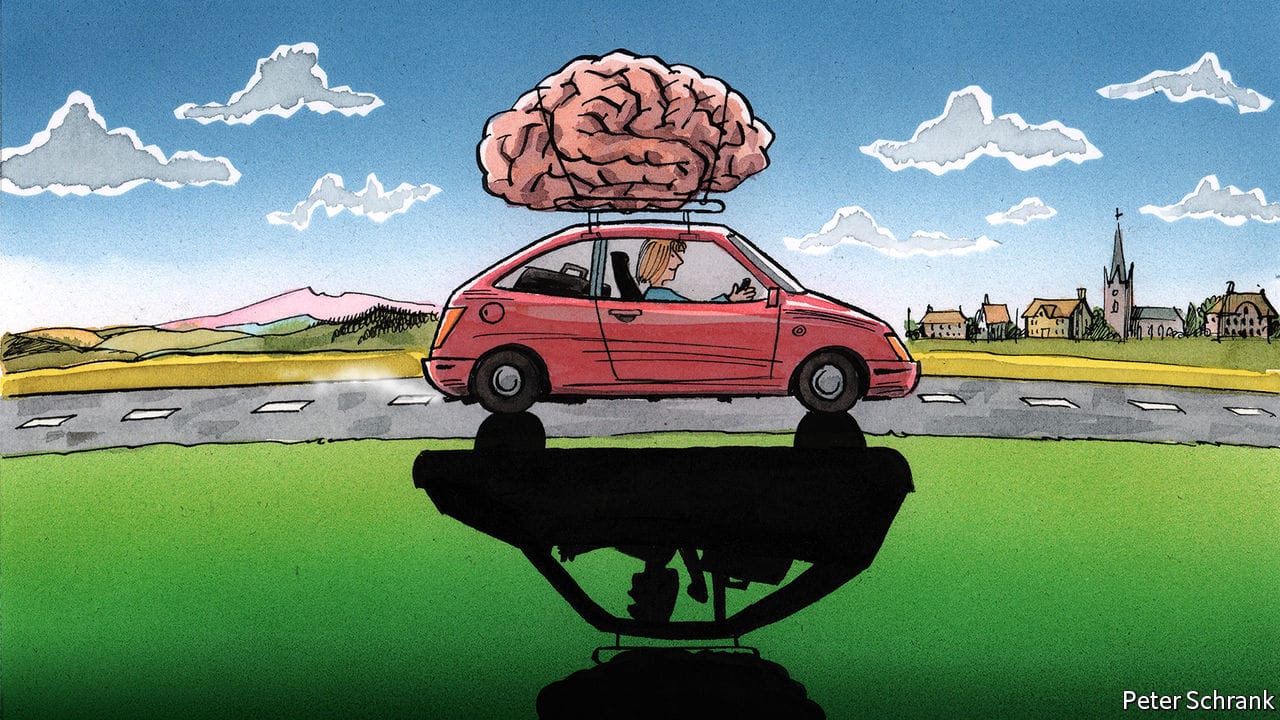

AFTER A DECADE in Britain, it took Alexej Kirillov barely 24 hours to decide to leave. In March 2020, as Europe’s borders slammed shut, Mr Kirillov, a 31-year-old strategy consultant, had a choice: lockdown in a costly, lonely London flat or go home to the Czech Republic and be close to family. “I was not planning to leave for another five years, or longer, or never,” he says. But covid-19 changed his mind. Nearly a year on, he has set up shop in his homeland. A temporary return has become permanent. “Now I’m back, I think why didn’t I move back sooner?”He was not alone. In 2020 Europe saw a great reverse migration, as those who had sought work abroad returned home. Exact numbers are hard to come by. An estimated 1.3m Romanians went back to Romania—equivalent to three times the population of its second-biggest city. Perhaps 500,000 Bulgarians returned to Bulgaria—a huge number for a country of 7m. Lithuania has seen more citizens arriving than leaving for the first time in years. Other measures show the same. In Warsaw, dating apps brim with returning Poles looking for socially undistanced fun. Politicians in eastern Europe had long complained of a “brain drain” as their brightest left in search of higher wages in the west. Now the pandemic, a shifting economy and changing work patterns are bringing many of them back. A “brain gain” has begun.