- by Yueqing

- 07 30, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

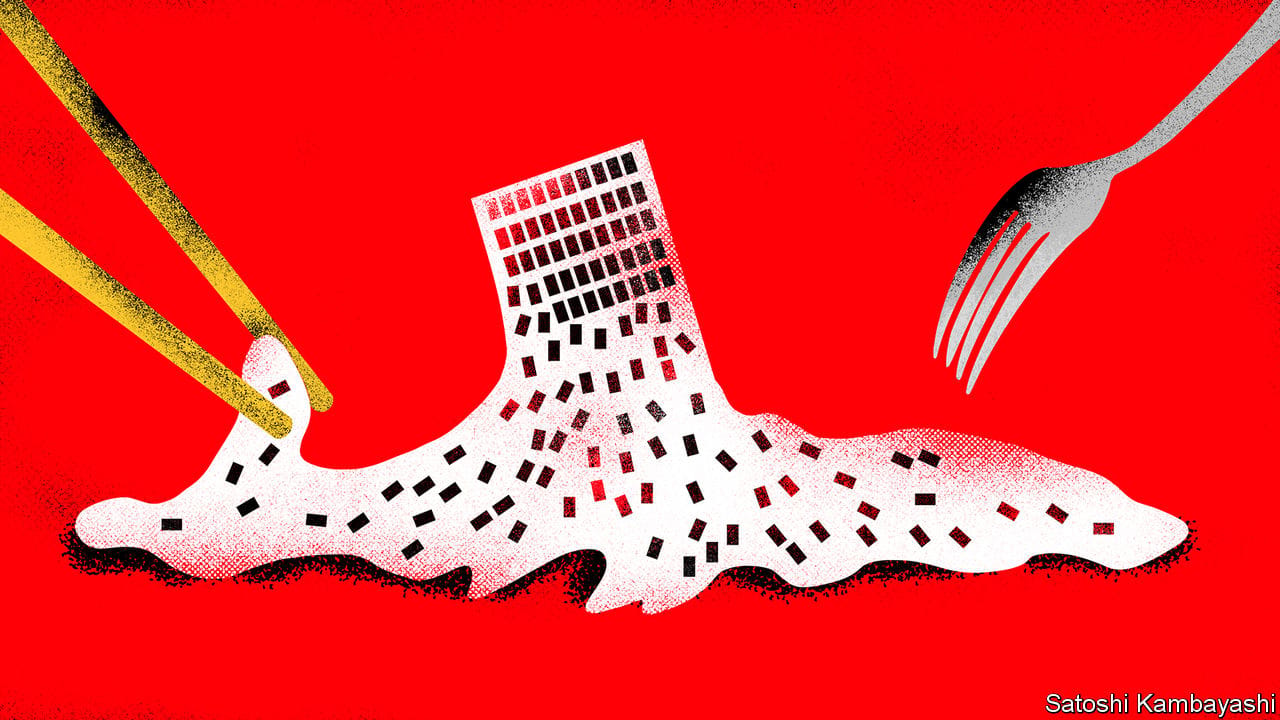

DISSIDENTS, SMUGGLERSVIE and rogue executives have been hiding out on either side of the 40km border between Hong Kong and China for generations. Despite being part of the same country since 1997, the two jurisdictions have separate legal systems with limited interaction. Chinese companies have crossed the border in droves since the 1990s to access global capital markets. Investors, trusting in Hong Kong’s independent legal system, have met them there, cash in hand. But when Chinese groups struggle to repay their debts, investors seldom attempt to chase them back over the border, where the bulk of the companies’ assets are located. Enforcing cross-border claims has been excruciatingly difficult and often futile. That could now be changing, with important consequences for creditors both at home and abroad.Global investors have long accepted the tenuous links between their money and Chinese assets. Take, for example, the legal structures known as variable-interest entities (s) that have been used to connect hundreds of billions of foreign investors’ dollars with Chinese-issued shares, despite having scant legal recognition in China. In the debt markets so-called keepwell deeds have thrived as a way of keeping offshore investors’ nerves under control. They are a type of promissory note that obliges parent groups to help pay back investors should an offshore subsidiary default. But no investor has ever successfully used these notes, which back some $90bn in dollar-denominated bonds, to force onshore companies to pay offshore debts. Creditor committees have been used to restructure debts that span the border. But more broadly it is rare that a Chinese court dealing with an insolvency case has recognised proceedings launched outside the mainland, including in Hong Kong.