- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

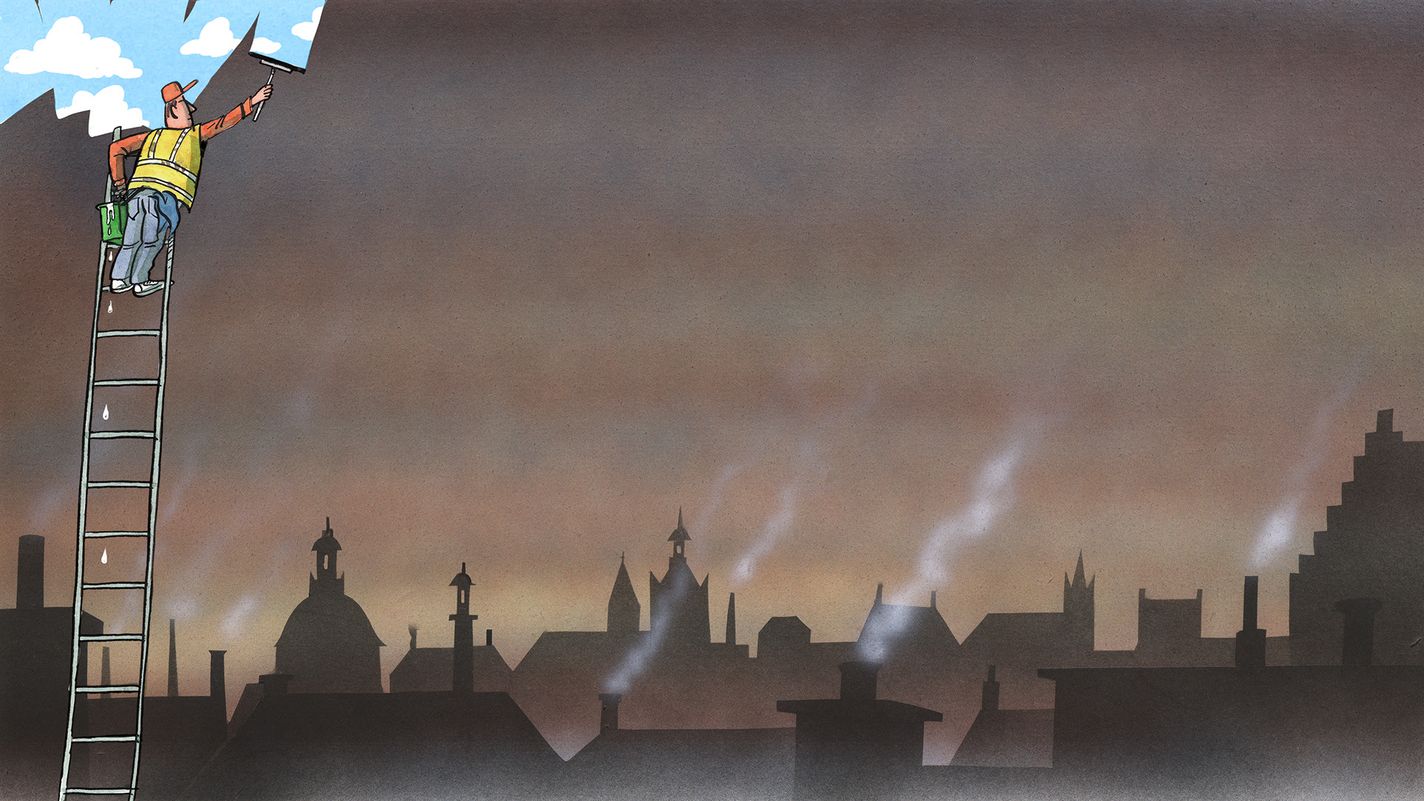

As autumn arrivedEUEU last year, the residents of Nowy Targ, a market town in southern Poland, were given an unusual tip to keep their homes warm in the midst of soaring energy prices. “One needs to burn almost everything in the furnaces,” said Jaroslaw Kaczynski, head of the ruling Law and Justice party, “aside from tyres and similarly harmful things, of course.” On a recent visit on a crisp spring day, with snow lingering on the ground, the evidence of locals having taken up Mr Kaczynski’s advice could be both seen and sniffed. Judging from the acrid smoke coming out of some chimneys, a few households may have even skipped the admonition about tyres. As the afternoon progressed and workers returned home to refill home furnaces ahead of chilly evenings, the mountains that skirt the town disappeared behind a dull haze. A bakery by the side of the road to the train station emitted a scent not so much of local delicacies as of combusted leather boots.Europe prides itself as a green kind of place, the land of 15-minute cities where residents bike from work to yoga classes. But many bits of Europe still stink—literally. Those virtuous cyclists weave their way through streets thronged with diesel engines. Farmers spew ammonia, a pungent gas, into the air. What industry remains is the source of sulphur compounds that harm nature. Perhaps most worryingly, generating energy from fossil fuels to keep homes heated results in invisible clouds of particulate matter which clogs human lungs. Across the , over 300,000 people die prematurely from poor air quality every year, according to the ’s environmental arm. That is nearly half the number of excess deaths caused by covid-19 in its first 12 months.