- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

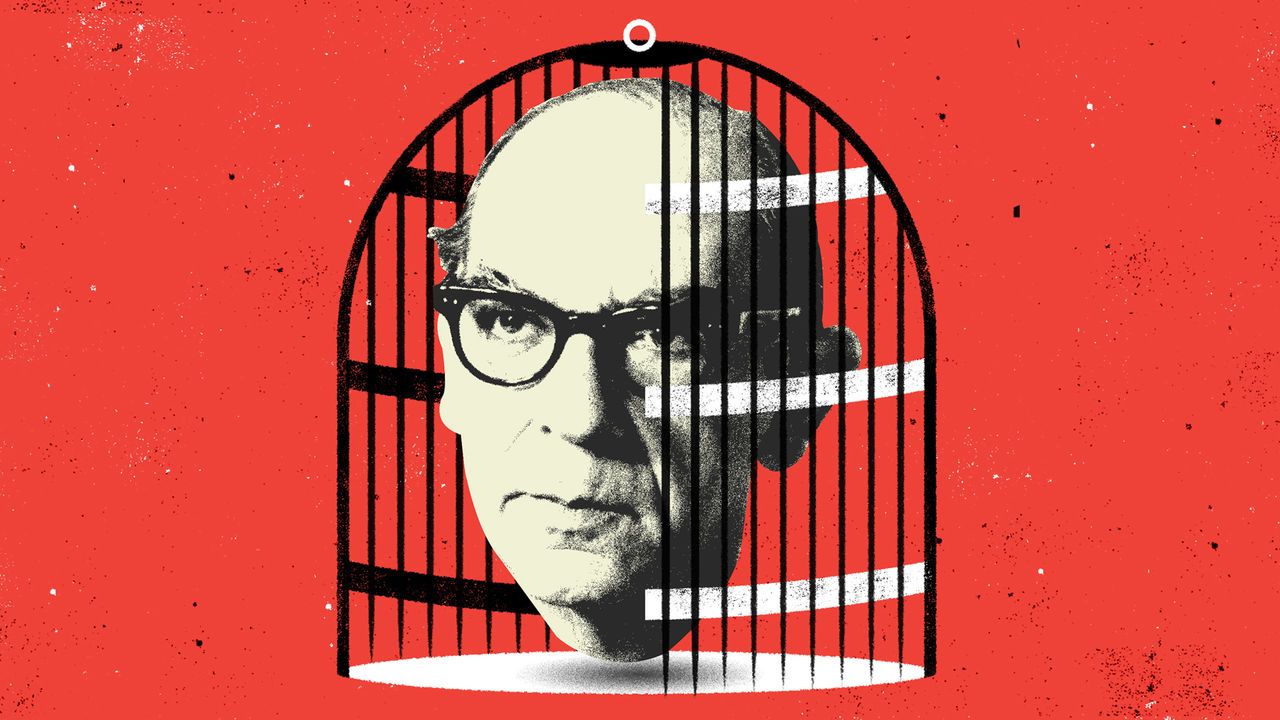

Sir Keir starmer MPMPwas born in 1962 in a Britain that was still cloaked in an austere, suppressive fug. The lord chamberlain censored plays. Abortion was outlawed, and divorce permitted only rarely beyond cases of adultery. Gay sex was a criminal act. This world was largely swept away before the future prime minister started secondary school. Individual liberties triumphed over collective moral prohibitions. My rights beat your qualms. is, for its advocates, the next and last step of this liberal revolution. A private member’s bill, brought before Parliament by Kim Leadbeater, a Labour , would give terminally ill patients in England and Wales a right to request their death. It will be debated in a second reading on November 29th but its chances of passing are unclear. On this issue Britain, once a pacesetter in liberalising legislation, is behind other Western countries. Why?The problem does not lie with the public, which has consistently supported change since the early 1980s. Nor does the cause of lack friends in high places: successive bills have been brought before Parliament since the first was debated in 1936. It remains unresolved because the debate on this issue is no longer a fight between the liberal idea of personal autonomy and a Christian idea of public morality. It has become a fight within liberalism, between two rival ideas of liberty.Isaiah Berlin, a political theorist, would have recognised this battle. In 1958 he delivered a lecture entitled “Two Concepts of Liberty”, which set out two big strands of . “Negative liberty”, or “freedom from”, was the ability of a person to do as they wished without interference from others. This was the realm of English thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Stuart Mill. It means the right to property, religion and speech beyond the grasp of the state.In contrast, “positive liberty”, or “freedom to”, said Berlin, was about “self-mastery” and the triumph of a person’s “higher nature” over his low impulses and outside influence. It reflected a sense of a deeper autonomy: “a doer—deciding, not being decided for, self-directed and not acted upon by external nature”. But, he went on, liberating people’s true will would invariably mean the state placing constraints on what they could legally do for their own benefit—just as children are compelled to go to school, even if they do not grasp why. In other words, negative and positive liberty were in conflict. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a Swiss liberal thinker, had said one could force people to be free. This, Berlin said, was the logic of paternalists, tyrants and Marxists.That lecture can serve as a guide to today’s debate. Ms Leadbeater and her supporters preach a negative liberty: picking the time and manner of your death is an essential question of freedom, choice and autonomy. Berlin argued that negative liberty requires privacy: “a frontier…drawn between the area of private life and that of public authority”. Liberals of the 1960s wanted the government to get out of the bedroom; advocates of assisted dying want it out of the hospice.Opponents of assisted dying cast their arguments in terms of autonomy and choice, too. Under Ms Leadbeater’s regime, they argue, patients would inevitably feel under pressure, implicitly or overtly, to end their lives. For the frail and sick who fear themselves to be a burden, argues Danny Kruger, a Conservative , “the conversation” about an assisted death would not be an expansion of liberty but a mockery of it, robbing the dying of the freedom that comes with knowing their nearest and dearest are not conspiring to kill them. This argument is a version of Berlin’s positive liberty: a constrained legal choice but greater real autonomy. For paternalists, the philosopher said, oppression was justified if it liberated the “‘true’, albeit submerged and inarticulate, self”.Post-war moralists approved of a strong state. Today’s opponents of assisted dying have a libertarian suspicion of it. Given the long list of geriatric-care scandals, the argument runs, the National Health Service seems all too good at finishing people off already. The idea of meaningful choice, on which the concept of negative liberty rests, is hard to apply to a bureaucracy that struggles to provide people with decent dinner options.In this clash of two liberties, listen to what the assisted-dying debate is not. God loomed over the bill in 1936: Lord FitzAlan, a former lord lieutenant of Ireland, declared it an impertinent usurpation of the Almighty. God’s presence was also felt the last time the Commons debated a bill on assisted dying, in 2015. (“Although some may believe that suffering is a grace-filled opportunity to participate in the passion of Jesus Christ, which is selfishly stolen away by euthanasia, I say ‘Please count me out’,” sighed Crispin Blunt, a Tory supporter of that bill.)But society is becoming more secular at a striking pace, as is the House of Commons. Christian groups know that if they relied on appeals to Christian ethics, they would lose. There is less talk of the sanctity of life and the moral injury of suicide, more focus on notions of “safeguarding” and “informed consent”.For advocates, Ms Leadbeater’s bill may turn out to be another missed opportunity. It has been hastily prepared. Sir Keir, despite his support for the cause, has decided to follow Harold Wilson, the Labour prime minister of his childhood, in being an aloof bystander rather than a participant. But the debate is inexorably shifting onto their preferred terrain. The argument has inched from moral prohibitions to policy design. It centres not on whether assisted suicide is tolerable but whether the British state is able to implement it. This clash of two concepts of liberty explains why the debate has persisted for so long. But a battle fought on liberal terms is also one the liberalisers will, in the long run, surely win.