- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

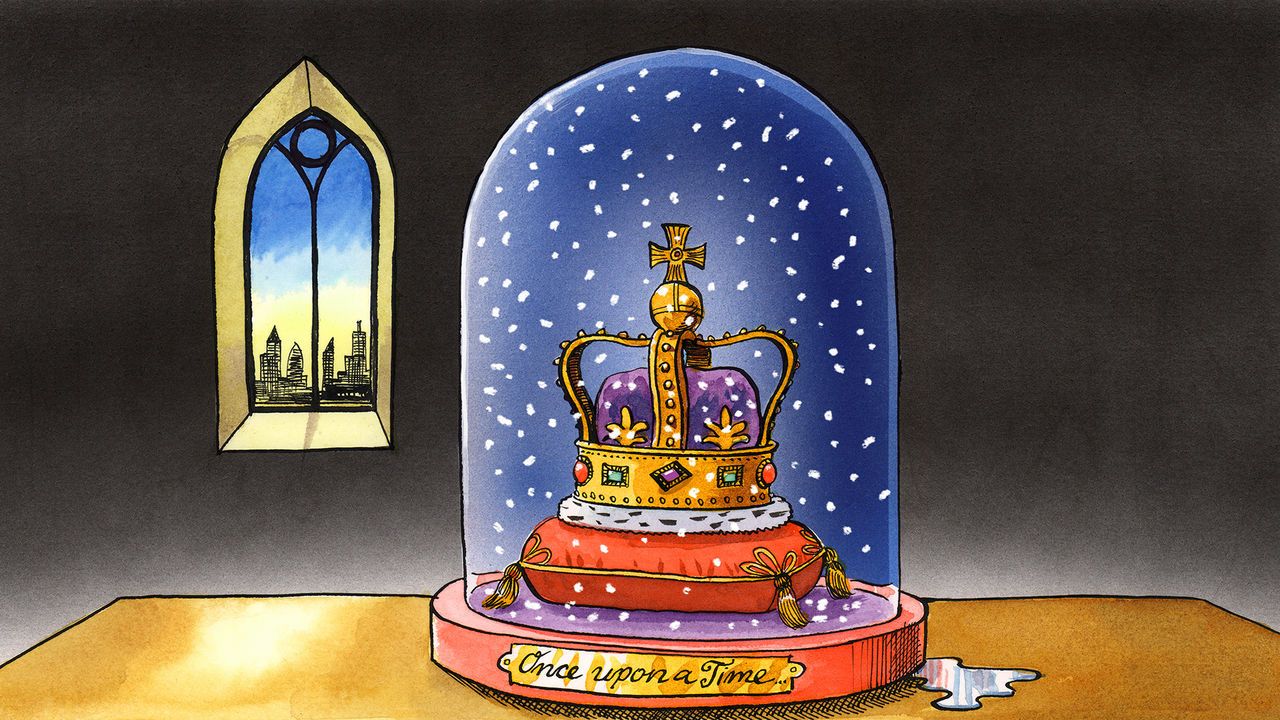

Francis II ascendedGPT. the French throne after his father took a lance in the eye at a jousting tournament in 1559. A century earlier James III became King of Scotland after his father had found himself unwisely standing next to an exploding cannon. Other princes got promoted as the by-product of a brother’s poisoning or an uncle’s beheading—a pity, to be sure. The ascension of Frederik X to the throne in Denmark on January 14th was a staid affair by comparison. A fortnight earlier his mother, Margrethe II, startled her subjects by announcing that 52 years on the throne was quite enough. Unbeheaded, unpoisoned and seemingly unflappable, she convened government ministers to witness her signing the instrument of abdication, then invited Frederik to take her seat at the Council of State. After uttering “God Save the King,” the 83-year-old shuffled out of the room and off the royal scene. Outside, cheering crowds awaited a glimpse of their new monarch.Every family has an heirloom which is too precious to throw away yet of little practical use. A dozen European countries have the constitutional equivalent. Kings, princes and one grand duke still rule over otherwise enlightened places mainly in northern Europe—think egalitarian Scandinavia, pragmatic Britain or no-frills Benelux. In an age of democracy none is elected; in an era striving for gender balance all now happen to be men; in these times of accountability many float somewhere above the law. They exude the mustiness of quill and parchment in an age of Chat Yet most monarchies have approval ratings their democratically elected counterparts might murder a parent for. Like the human appendix, Europe’s royal highnesses are essentially vestigial: they serve little obvious purpose, but few think there is much reason to excise them until they cause trouble.