- by Yueqing

- 07 30, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

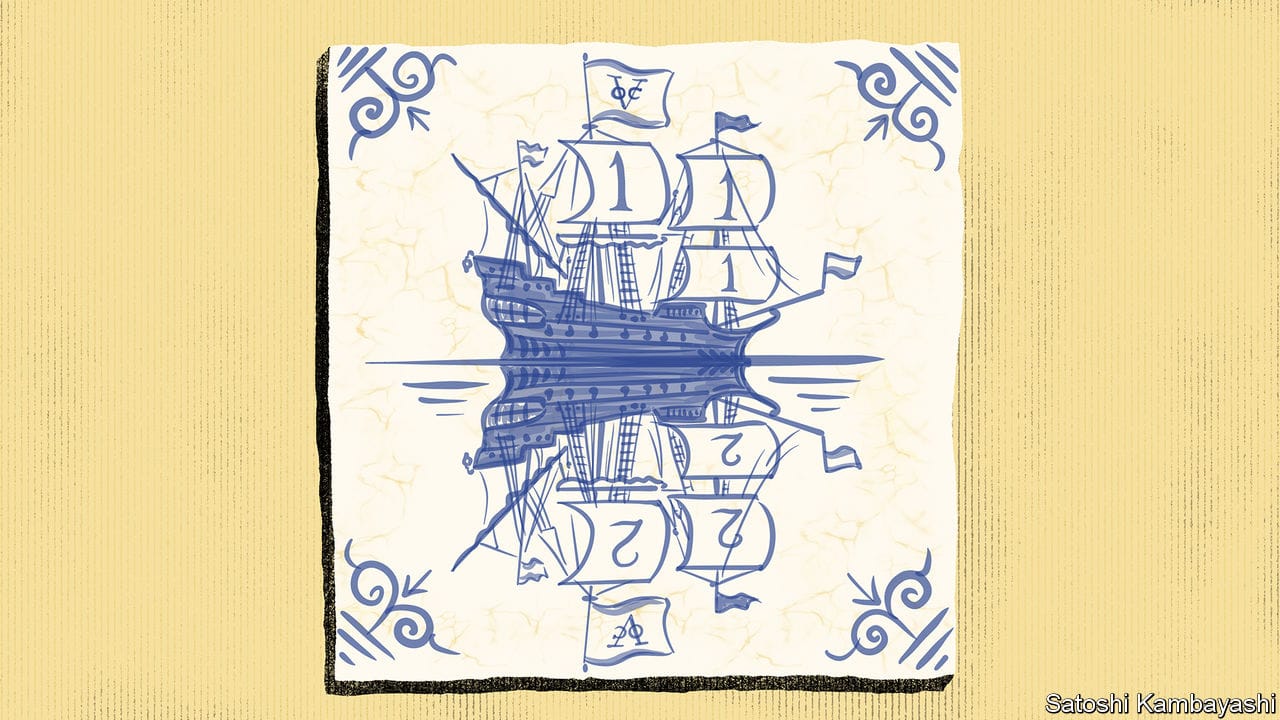

AT MIDNIGHT ON August 31st 1602, the public offering of shares in a new kind of enterprise closed. The charter for the venture, the Dutch East India Company, granted it a monopoly on trade with Asia until 1623, at which time, it was assumed, the firm would be liquidated. Twenty-one years is a long wait for capital to be returned. Smaller maritime ventures were generally wound up and the spoils divided after three or four years, when (and if) the ships returned. So shareholders were given an option to cash out after ten years. It hardly mattered. A faster exit route soon opened up.The merchants who gathered daily around Amsterdam’s New Bridge to trade spices and grain proved as willing to buy and sell shares. These developments are recounted in “The World’s First Stock Exchange”, by Lodewijk Petram, a historian. One of the book’s many lessons is that wherever there is a primary market for a new kind of asset, there will soon be a secondary market.