- by

- 07 24, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

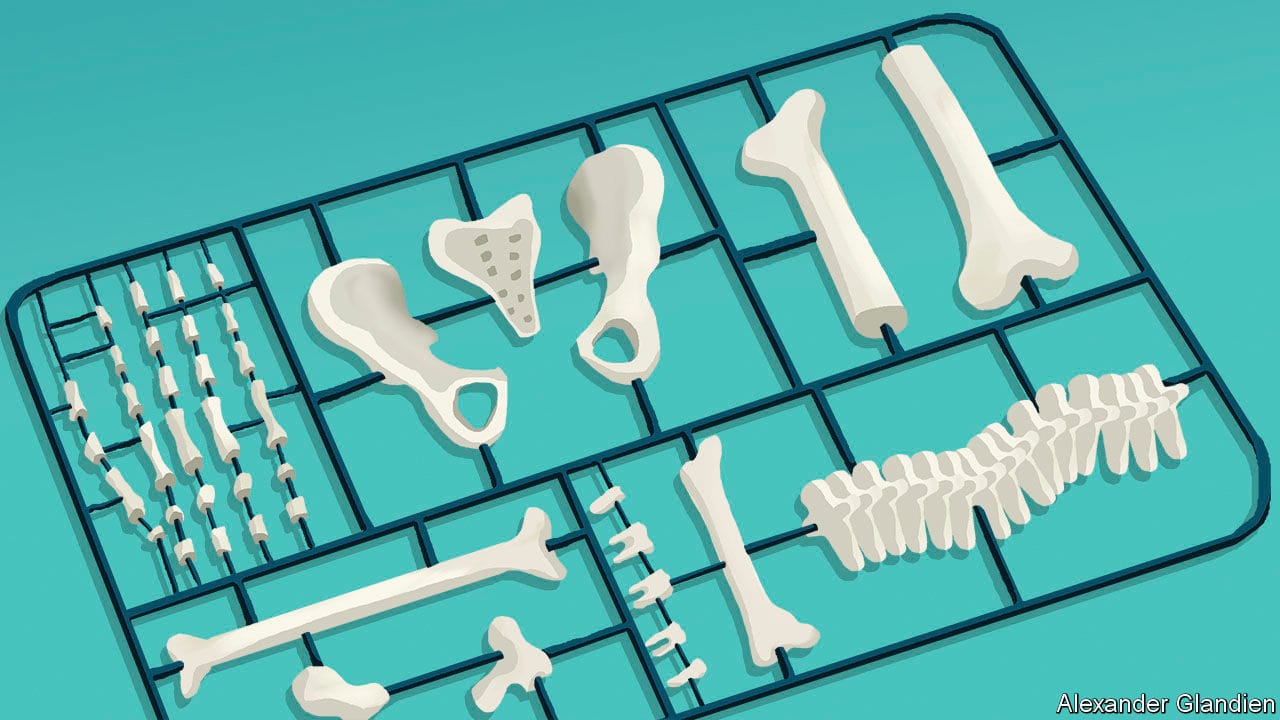

A ROBOTIC LAWNMOWER3D3D3D keeping the grass neat and tidy outside a modern industrial building in Carrigtwohill, near Cork in Ireland, is a good indication that something whizzy may be going on inside. And so it proves. The airy production hall contains row after row of printers, each the size of a large fridge-freezer. The machines are humming away as they steadily make orthopaedic implants, such as replacement hip and knee joints. Even though several hundred employees’ cars are parked outside, the hall is almost deserted. Every so often a team appears, a bit like a Formula One pit crew, to unload a machine, service it and set it running again to make another batch of implants.It is not unusual in modern, highly automated plants to find the workforce distributed like this, with most of them in the surrounding offices engaged in engineering tasks, logistics, sales and so on, rather than on the factory floor. But this two-year-old factory, owned by Stryker, an American medical-technology company, differs from conventional manufacturing in another way as well. It is an example of how printing, which a decade ago was seen by manufacturers as suitable only for making one-off prototypes, is quickly entering the world of mass production. For commercial reasons, Stryker keeps some of the details secret. But the factory, the largest -printing centre of its type in the world, works around the clock and is said to be capable of producing “hundreds of thousands” of implants a year.