- by

- 07 24, 2024

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

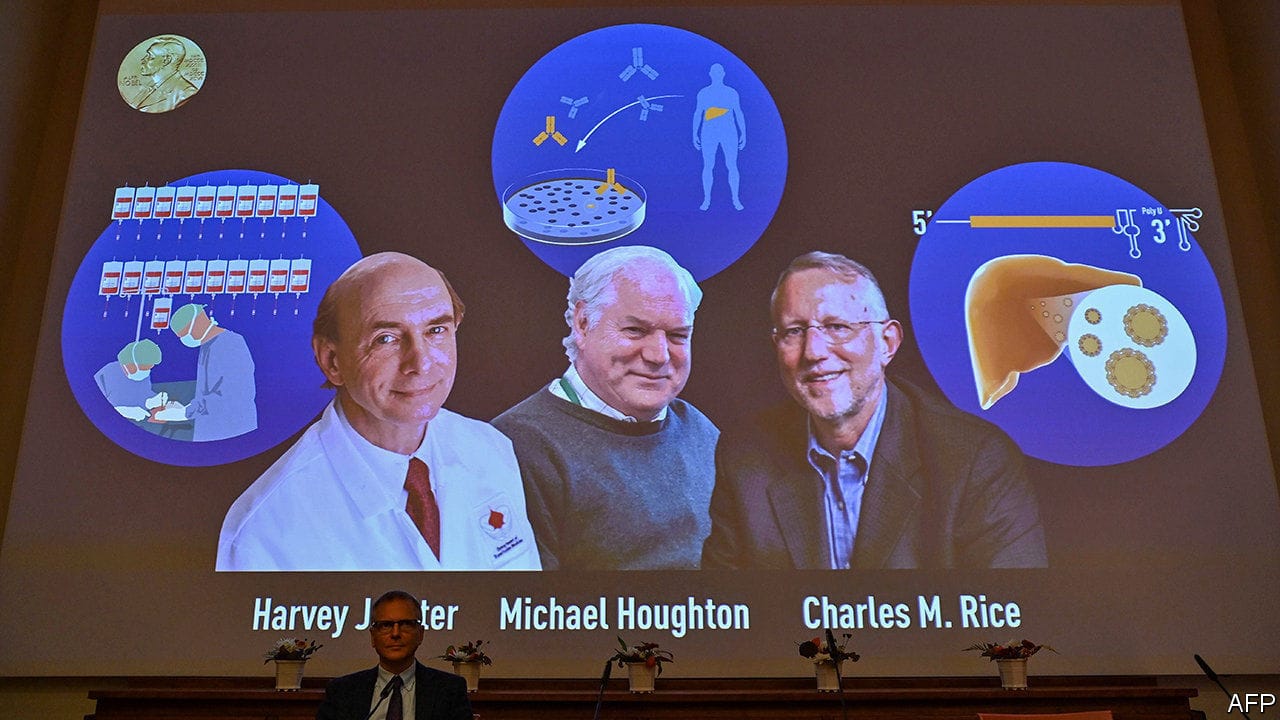

THIS YEAR’S Nobel prize for physiology or medicine went to three of those involved in identifying the hepatitis C virus, which causes life-threatening infection of the liver and is passed on by exposure to contaminated blood. Though other widespread lethal infections such as malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis gain more attention, the World Health Organisation reckons that around 70m people are infected with hep C and that it kills 400,000 people a year. Hep C has also, in the past, turned the business of blood transfusion into a lottery, since there was no way to tell whether a particular batch of blood harboured it. That this is no longer the case is, in no small measure, thanks to the work of this year’s laureates—Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles Rice.Dr Alter’s work came first. In the 1960s he was a colleague of Baruch Blumberg, who discovered the hepatitis B virus (for which he won a Nobel prize in 1976). Hepatitis viruses are labelled, in order of discovery, by letters of the alphabet. “A”, a water-borne pathogen, causes an acute infection that passes after a few weeks and induces subsequent immunity. The effects of “B” and “C”, though, are both chronic and may result eventually in cirrhosis and cancer. Blumberg’s discovery led him to a vaccine for hep B, and also meant that blood intended for transfusion could be screened. But it became apparent that such screened blood still sometimes caused hepatitis, albeit at lower rates. Since hep A was also being screened for by this time, that suggested a third virus awaited discovery.