- by

- 01 30, 2025

-

-

-

Loading

Loading

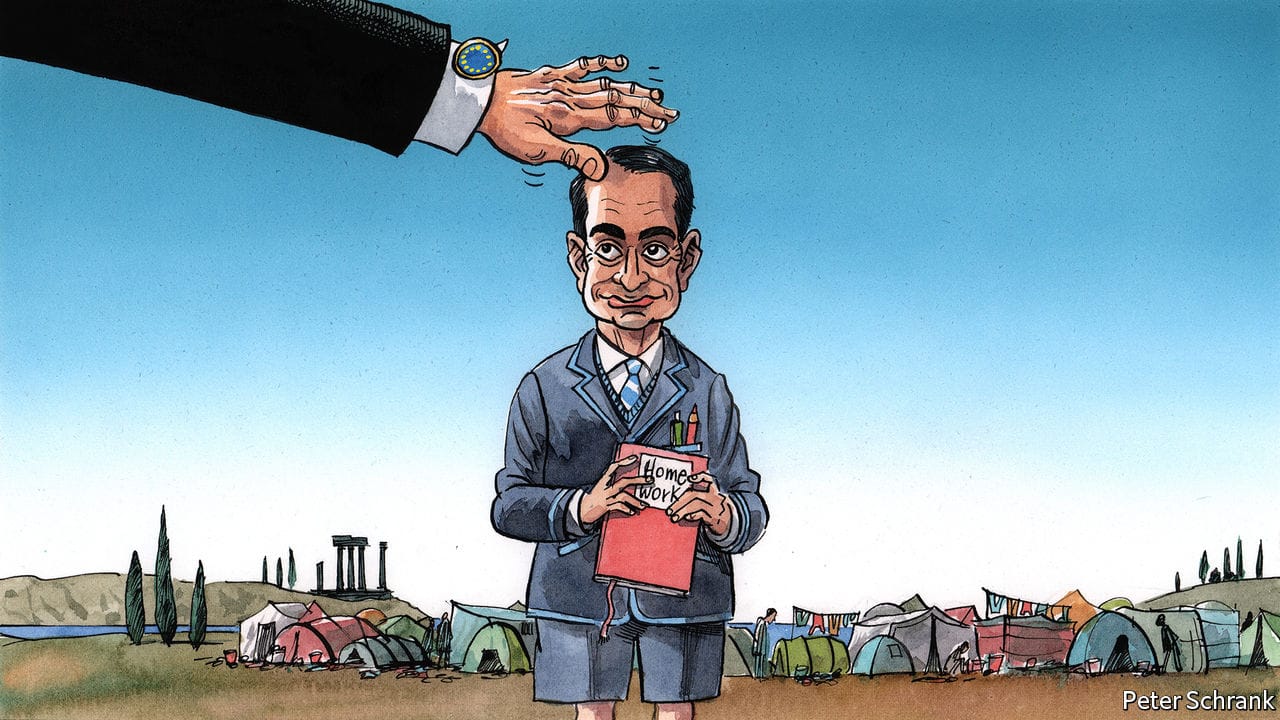

BRUSSELS CANEUEUEUEUEUEU be a patronising place. In the , prime ministers are sometimes treated like schoolchildren. In a favourite phrase, stern officials declare that national governments must “do their homework”. If Brussels is a classroom, then Greece has become an unlikely swot. Its handling of the pandemic has been praised. Its plans for spending a €31bn share of the ’s €750bn ($915bn) recovery pot got a gold star from officials. Greek ideas such as a common covid-19 certificate are taken up at a European level. After a decade in which Greece found itself in remedial lessons, enduring three bail-out programmes and economic collapse, it is a big shift. Syriza, the leftist party that ran the country from 2015 to 2019, was the class rebel. By contrast, the government of Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the smooth centre-right prime minister since 2019, is a teacher’s pet.Partly, the change in reputation is a question of politics. Syriza set itself up as a challenger to the ’s current order, hoping to overhaul the club from the inside. But if the has a house view, it is one of the centre-right where Mr Mitsotakis’s New Democracy sits. In the technocratic world of politics, Mr Mitsotakis fits right in. A former management consultant, he speaks English, French, German and Davos, a dialect used by middle-aged men in snowboots at high-altitude conferences. He wears the school uniform well. Explicitly, New Democracy was elected in 2019 on a plan to overhaul Greece. Implicitly, their task was to make Greek politics boring and turn Greece into a normal European country. Syriza’s leaders saw themselves as a beginning of history; New Democracy’s leaders see their job as bringing a dark era to an end.